Luke Bates, Automotive Analyst at the Advanced Propulsion Centre (APC) explores the compelling opportunities for the UK hydrogen and fuel cell supply chain.

A question we often get asked at the Advanced Propulsion Centre (APC) is “What’s the next big thing in automotive technology?”. Perhaps that question needs to be rephrased; maybe the next ‘big thing’ isn’t new at all.

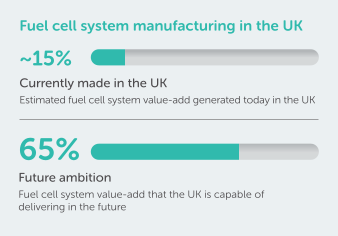

In fact, for the UK, what we should be looking out for isn’t technology, but opportunity – because what we’ve found in the process of creating our most recent publication – our fuel cell system value chain maps – is that our ambition could be much greater.

The past few years have seen hydrogen gaining momentum as the clean fuel of the future: simple, abundant, reliable. This shift has brought about a step change for fuel cells, and we are seeing strong signals that now is the time to scale up domestic hydrogen and fuel cell industrialisation.

The new generation of proton exchange membrane (PEM) hydrogen fuel cells are compact, lightweight, and offer high power density, making them attractive for vehicle applications – not as a competitor to battery electric vehicles (BEV), but playing a complementary or supplementary role as we’re already seeing in heavy goods vehicles and vans. The cost of automotive fuel cells has fallen by 70% since 2008 and increased production is bringing costs down further. With the new Toyota Mirai, Hyundai launching both cars and trucks, joint ventures between Mercedes and Volvo, and Stellantis’ hydrogen vans coming to the UK in 2023, there’s increased focus on bringing this technology to the mass market.

Total cost of ownership (TCO) is critical for heavy duty and commercial applications, where ‘time is money’ couldn’t be more literal. This is where fuel cells become the decarbonisation frontrunner: reliably delivering an enormous amount of energy, without excessively compromising payload and charging downtime – a trifecta that a pure battery electric powertrain cannot yet deliver.

Range versatility is also an appealing proposition for the light commercial and passenger vehicle sector, where we are seeing more powertrain synergies between battery and fuel cell technology. This is already happening for small and mid-sized trucks. For example, new entrant Tevva’s 7.5t to 19t delivery trucks run on battery-power supplemented by a fuel cell system for additional range and versatility. The hybrid solution is lighter, more cost effective than a pure BEV and achieves TCO parity with diesel variants within 35,000 miles.

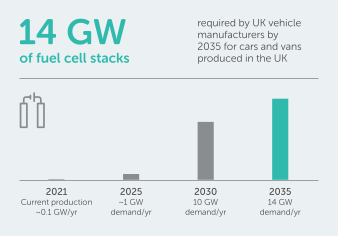

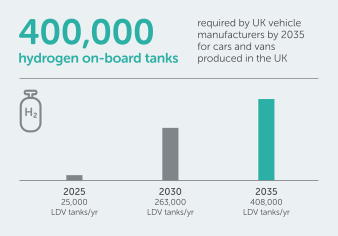

Technological advancements are bringing forward the commercial viability of lighter fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs), which then begins to dictate the volumes and ramp-up needed across the industry. We forecast rapid growth in fuel cell platforms for light duty vehicles from 2030 as hydrogen refuelling networks expand and hydrogen at the pump drops to $4-5/kg. We expect that 14GW of on-board fuel stack power and 400,000 hydrogen carbon fibre will be required to meet the demands of FCEV production in the UK alone by 2035. This is where we start to see the green shoots of that ‘next big opportunity’

Reference: https://www.apcuk.co.uk/how-the-uk-government-hydrogen-strategy-can-succeed-for-transport/

Getting ahead of the hydrogen fuel cell growth curve

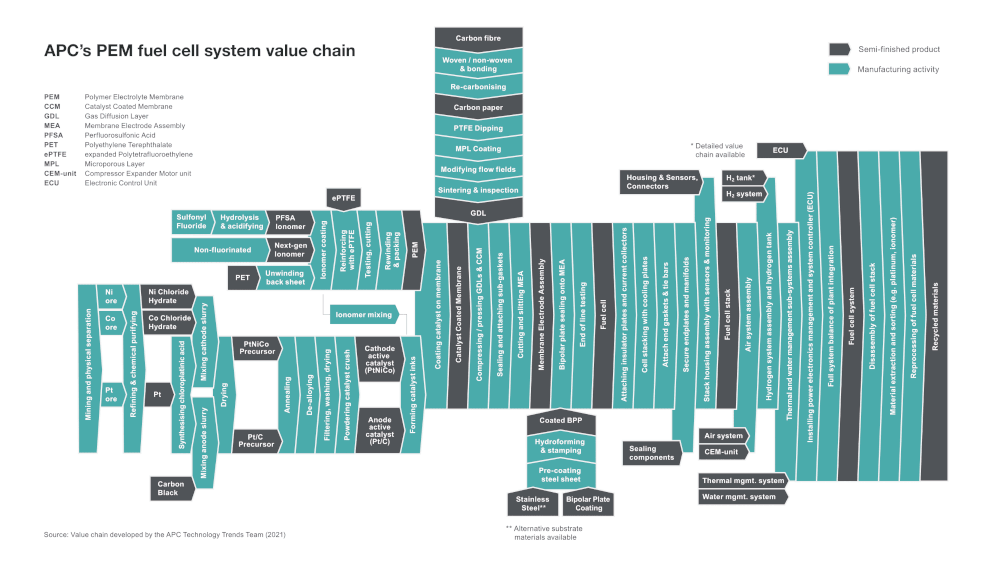

The fuel cell stack is the heart of a fuel cell power system producing DC current to drive the electric motor. High pressure hydrogen tanks, typically 350 or 700 bar, store the gas in multiple carbon fibre wrapped cylinders on-board the vehicle. The UK has strong grass roots in both fuel cell stacks and carbon fibre technology.

Our analysis shows that the UK has the potential to become one of the world’s fuel cell system production capitals. Currently UK companies contribute to around 15% of the value-add in a fuel cell system, but by leveraging capability and further investment, APC believes that ambition could be 65% of the entire fuel cell value chain radiating from UK businesses.

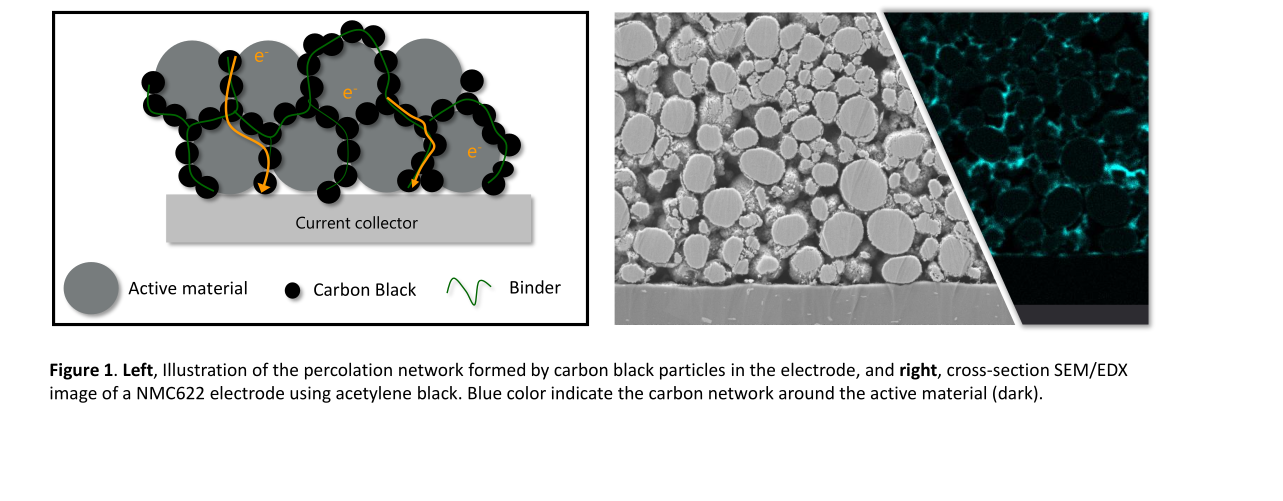

There are three main areas to achieving this goal: membrane electrode assembly (MEA), fuel cell stack assembly and hydrogen tank production. These are less capital intensive than battery production investments and closely match the skills and expertise of current vehicle and engine manufacturing. Like battery cell manufacturing, localising fuel cell and stack assembly is a key intermediate step that connects the catalyst coated membrane supplier with the OEM. Since fuel cell stack assemblies are less complex than internal combustion engines, it should be possible to transition UK’s rich heritage and capability in engine manufacturing to fuel cells and safeguard hundreds if not thousands of highly skilled jobs.

Why is this a big opportunity for the UK?

The automotive fuel cell market offers the UK an opportunity to lead in Europe and be recognised internationally as a centre of excellence in fuel cell system manufacturing. Getting ahead of the curve has proven to be critical in the lithium-ion battery market and this will be the same for fuel cells – first movers have to be ambitious to reap the rewards in the long-term.

To help with this ambition, the APC’s fuel cell and hydrogen tank value chain maps enable suppliers to look upstream and downstream from their current capabilities, identifying potential growth opportunities across the value chain.

It is no secret that the UK’s current strengths are in the upstream stages of fuel cell system manufacturing – the electrochemical and material processing on the left – thanks to the engineering nous of leading players like Johnson Matthey and Technical Fibre Products (TFP).

Johnson Matthey’s position in the fuel cell market is unique because they can leverage their world-leading market position in secondary platinum refining and recycling from spent automotive catalytic converters. Platinum is a critical metal used in catalyst coated membranes, the core of the MEA. This, together with the fact they also manufacture their own proton exchange membrane (PEM), means they have in-house manufacturing of most of the high-value ingredients that make up an MEA. Understanding their strengths in fuel cells but also in the wider hydrogen value chain, Johnson Matthey recently pledged £1 billion investment in clean hydrogen technologies by 2030, which signals confidence in the growth to come for UK manufacturing.

Perhaps less well-known, TFP are a major global supplier of carbon paper, which is the advanced material used in the gas diffusion layers of an MEA. They draw on decades of paper-making capability from their parent company James Cropper to manufacture high quality carbon paper already being used in FCEVs on the road today. TFP have recently launched TFP Hydrogen Products, adding catalyst powders and further electrochemical expertise to their offering.

This upstream expertise represents highly valuable intellectual property for the UK – and our mission now is to anchor this in the UK to build a thriving material supply chain that can grow and innovate, maximising opportunities from the growth of fuel cell systems in automotive applications.

As such, there is definitely value in building towards the right-hand side of the value stream –to the next steps of fuel cell stack and system assembly and the high-pressure carbon fibre cylinder tanks essential to the on-board storage and transportation of hydrogen. APC is working with several companies in these specific areas, piecing together the conversations and learnings across multiple sectors – not just automotive.

For us, collaboration is key, and a vital part of the role we play in the UK’s net-zero journey. Thankfully, we are seeing traction; Canadian fuel cell manufacturer Ballard Power’s acquisition of UK company Arcola Energy (now Ballard Motive Solutions) in the last quarter of 2021 is a prime example. Arcola has been integrating the Ballard fuel cell systems into buses, refuse trucks and trains for a decade, ultimately attracting Ballard’s attention and a $40 million inward investment in UK manufacturing.

Similarly, Intelligent Energy assemble automotive PEM fuel cells and stacks in the UK and are currently active in APC-funded project ESTHER looking to optimise and commercialise their automotive fuel cell stack through collaboration with leading Chinese vehicle manufacturer Changan.

The final element to reach that 65% ambition is to scale up UK manufacturing of automotive hydrogen tanks and carbon fibre, which account for around a third of the total fuel cell system value. UK headquartered Luxfer are currently the leading supplier of automotive hydrogen tank systems in Europe, and they supply into the Hyundai Xcient fuel cell truck programme. Attracting capital investments in UK tank manufacturing relies on strong demand signals from UK vehicle manufacturers, but as we have already established, we are seeing momentum here, particularly in fuel cell electric buses and off-highway machinery.

We will continue to work closely with government, industry, and academia to realise this ambition of 65% value-add in the UK. The difficult lesson we’ve learnt in scaling up battery production, after leading battery cells research in the 80’s and 90’s, is that we could get caught out sleeping-at-the-wheel whilst others overtake us. Early action and investment is needed to retain the UK’s leading innovation position and expand this to manufacturing activities if we are to deliver economic benefits to our industrial heartlands.

Luke Bates, Automotive Analyst Advanced Propulsion Centre (APC)